April 4 is one of the saddest days of the year. On that day in 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. While many events are held each year to honor Dr. King’s memory, too often people forget – or have never learned — why he was in Memphis that spring. Dr. King went to Memphis to help striking sanitation workers – and paid for his stand with his life. That makes April 4 an important anniversary not only in African American history (and in U.S. history in general), but in the history of the labor movement as well.

On February 12, 1968, hundreds of Memphis sanitation workers went on strike. At the time, they were making less than $1 an hour and were eligible for welfare. They decided that they had had enough of poor wages, terrible working conditions, and a viciously anti-union mayor.

The workers were members of Local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). The strike was the culmination of years of mistreatment. The workers worked 12 hours a day carrying garbage with busted, leaking pails. Some of the pails were infested with flies and maggots, and the workers had no place to wash up in the yard when they had to leave the trucks. Some of the workers had no running water when they returned home after work. The workers had no real benefits of any kind.

This dire situation came to a crisis point on Feb. 1, 1968, when the accidental activation of a packer blade in the back of a garbage truck fatally crushed workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker.

Almost 1,400 sanitation workers joined the strike. They shut the city down.

The workers and their supporters marched daily to pressure the mayor and the city council to recognize the sanitation unit under AFSCME Local 1733. The men wore signs which read “I AM a Man,” a slogan that was eventually recognized around the world.

Tension grew in the city as Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb called the strike illegal and threatened to hire new workers unless the strikers returned to work. On February 14, the mayor issued a back-to-work ultimatum for 7 a.m. on Feb. 15. The police escorted the few garbage trucks in operation. Negotiations broke off. The newspapers began to report that more than 10,000 tons of garbage was piling up.

It was in that tense environment that AFSCME organizers appealed to Dr. King to come to Memphis to speak to the workers. Initially, King was reluctant. He was immersed in work preparing for the Poor People’s Campaign. This was a huge undertaking, an effort to bring poor people of all ethnicities to Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1968 to protest poverty. But when AFSCME organizer Jesse Epps pointed out that the fight of the sanitation workers in Memphis was part of the same struggle as the Poor People’s Campaign, King agreed.

Once in Memphis, King immediately grasped the importance of what was unfolding there. On his first visit to the city, March 18, he spoke to a crowd of 17,000 people, and called for a citywide march.

On Thursday, March 28, King led a march from the Clayborn Temple, the strike’s headquarters. The march was interrupted by window breaking at the back of the demonstration. The police moved into the crowd, using nightsticks, Mace, tear gas – and guns. A 16-year-old, Larry Payne, was shot dead. The police arrested 280 people, and reported about 60 injuries. The state legislature authorized a 7 p.m. curfew and 4,000 National Guardsmen moved in.

On Friday, March 29, some 300 sanitation workers and ministers marched peacefully and silently from Clayborn Temple to City Hall – escorted by five armored personnel carriers, five jeeps, three huge military trucks, and dozens of National Guardsmen with their bayonets fixed.

In the last days of March, King cancelled a planned trip to Africa and made preparations to lead a peaceful march in Memphis. Organizers working on preparations for the Poor People’s Campaign in other cities were directed to leave those cities and come to Memphis, for it was clear that the Poor People’s Campaign could not be won without winning the fight in Memphis.

On April 3, 1968, Dr. King returned to Memphis. That evening, he gave an extraordinary speech to hundreds of people at Mason Temple. The speech has gone down in history as the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. Anyone who reads it today will notice that it is an eloquent statement of support for the sanitation workers. (That night, King called them “thirteen hundred of God’s children here suffering.”) But it is also a farewell speech, the oration of a man who knew he might not have long to live, and who was searching his soul to make sense of his life, and his place in history.

In the speech, King emphatically rejected the calls not to march again because of an injunction:

“[S]omewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of the press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right!”

At the end of his remarks he referred indirectly to the underhanded attempts by racists, the FBI, and other forces to sabotage his leadership and destroy the movement, declaring:

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like everybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

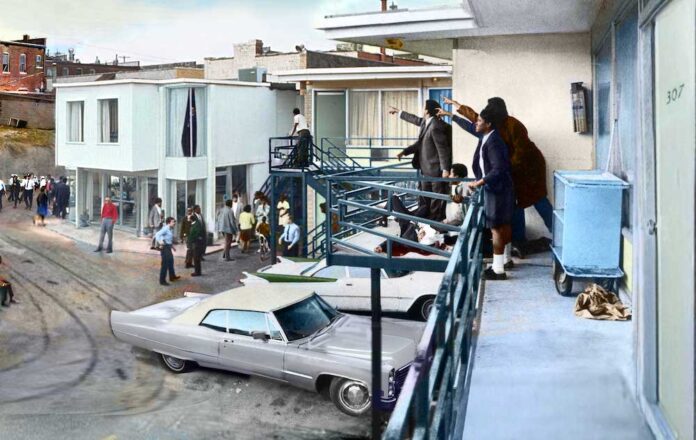

Less than 24 hours after uttering those words, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead while standing on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Urban rebellions broke out in more than 60 cities. In response to pressure from all over the country, the federal government sent Labor Department officials to Memphis to mediate a settlement to the strike.

On Tuesday, April 16, AFSCME leaders announced that an agreement had been reached. The agreement included union recognition, better pay, and benefits. The strikers voted to accept the agreement.

It was a bittersweet end to a long battle. The strike ended in victory, but at a terrible cost, the death of one of the foremost symbols of the fight for justice in that (or any) era. AFSCME’s victory in Memphis inspired other workers in Memphis to join unions, and other employees throughout the South to join AFSCME. The Poor People’s Campaign which Dr. King had been working on when he went to Memphis did take place later in the tumultuous year 1968. As King had hoped, it brought together poor people of all ethnicities to demonstrate in Washington, D.C. – African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and whites.

Given Dr. King’s role in the Memphis sanitation strike and the tremendous community support that the strikers received, perhaps the month of April ought to be a time to remember that not all labor leaders have an official position with a union — and that labor comes in all colors, and includes both employed and unemployed people. If we hold on to those lessons, we will honor what was won with such great sacrifice in Memphis in April 1968.